During my days as a photography student, many years ago, I was always challenged by studio work. It wasn’t the studio per se—the space, the lights, the props—that disquieted me. Rather, it was how all those aspects were to be brought together in front of my camera’s lens. I felt inadequate in this challenge so much so that I focussed my photographic efforts on subjects outside the studio. I went outside into the streets looking for scenes, objects, people, activities whose nature, arrangement or lighting caught my eye. And those I imaged.

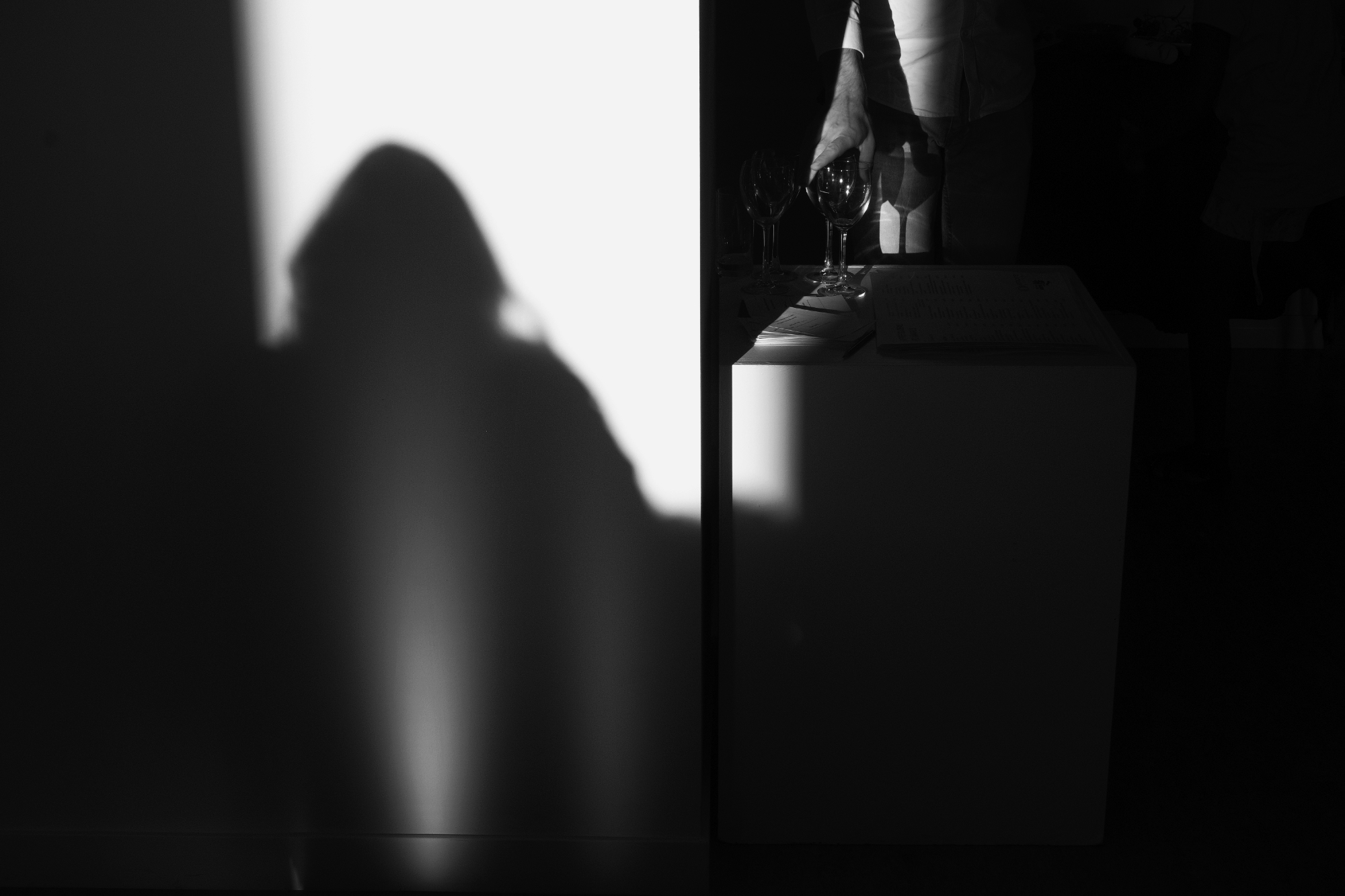

Over the years I developed a nomenclature for much of my style of image making. The smallish, often unnoticed, objects I imaged I called extracts. Extracts were captured and removed from their context—time, location, culture—and isolated onto various sizes and types of photosensitive material. Extracts—the unusual, the familiar, decontextualised, isolated—were what really piqued my attention.

They still do.

And, in my older age, after much deliberation about the nature of photographs, I decided they required a new nomenclature, one better reflective of their nature: moments of place or extracts of time.

For what is a photograph but a moment of time recorded, a scene extracted from its context. Time is stilled, excised from our perception of its flow, forever preserved. As was the scene, so shall be the image, forever (notwithstanding any subsequent artistic manipulation).

Extract or not, all photographs are subject to a post-exposure culling. Many images (under exposed, blurry etc) are simply and easily discarded, deleted from a memory card or hard drive (or thrown into the bin if on film). Others lie deeply buried in islands of ones and zeros, perhaps listed in a catalogue, perhaps not. They are abandoned: existing but not wanted or needed, accessible but not sought. A select few images experience a brief flurry of interest: printed, shared, published.

Whatever their disposition, a photographic collection contains a history of its creator’s awareness, a timeline of the locations visited, a sequence of interactions with the world. In short, photographs are our past, documented in fractions of seconds, our own, personal, moments of place, our individual extracts of time, excised from the trajectory of life leading towards our ultimate end.

Life—all life—abounds outside the studio, in the streets, beyond the towns, in dark alleyways and on bright sands. As a photographer we document what appeals to us; we take instants of time and place and give them an external existence. And in doing so the images say more about us than they do about their subject.

So here’s to extracts.