Our interactions with art—viewing, listening, contemplating, sometimes participating—are influenced by the context in which the art is experienced. Galleries (usually) are both the venue for experiencing art and the context for that experience.

Let’s ignore for the moment our own experiential context: our emotional state, our familiarity with the gallery and its collection, the style of art or artist experienced, our likes and dislikes in art etc. These factors all affect our experiences when interacting with art. And to keep things simpler still let’s just talk about art experienced in public galleries.

Our interactions with art are mediated by three factors: the location of the art (its venue: gallery location, building design, room design, distance travelled to experience it, ease of access to the venue, etc); its presentation (how it is displayed, its mounting, illumination etc); and its surroundings (nearby works, room colour scheme, signage etc).

Many galleries, themselves, have pretensions of being ‘arty’, of being exemplars of good design and as providing a positive experience for their patrons, donors, supporters, visitors and collected artists alike. In consequence, they are not simply containers for art and venues for its experience. Indeed great public art collections are held (and must be held almost by necessity) in buildings of great architecture. Greatness is achieved through gallery design, construction, use of glass, steel, concrete or stone. Such greatness is intended to complement the collection of art but never to outshine it (well almost never), irrespective of awards gained by the container.

Lesser public galleries, operated by local councils, community groups or individuals, seldom have the same greatness in their physicality as do the great public galleries. Lesser galleries, while they may be purpose designed and built or be simply repurposed buildings, create a quite different experience from that had in the great galleries. Similarly, lesser galleries also tend to have lesser art, being defined of course depending on one’s interpretation of ‘greater’ and ‘lesser’ and one’s preferences for art disciplines and styles.

Even so, lesser galleries have adopted an internal context—design, layout, presentation mode etc—that parallels, to a greater or lesser extent, that of their greater siblings. White walls (usually, or bare concrete), soft/dim lighting, open gallery spaces, artworks hoisted to eye level (whose eyes dictate that standard?), cool air, limited natural light and occasional benches or designer seats for contemplation of the art by the experiencer. Resources available to these lesser galleries largely determines the extent of the parallel.

Naturally, all these characteristics are intended to facilitate a worthwhile and meaningful experience while in the gallery. Mostly they do, but not always.

In some cases, the works of art essentially replace walls, so numerous are they, while sculptures and installations clutter walkways. Eye level hangings are generally inappropriate for children, taller people or those in wheelchairs. The air can be too cold, the lighting too dim, the seats too hard, navigation through the gallery can be confusing, signage can be written for the art connoisseur but not the uninitiated.

Then there is the monetary cost of interacting with art in galleries. Entry fees too often extract from a family budget more than can be afforded prohibiting any visitation/participation and hence interaction. Parking—cost and availability—similarly can be a dissuader of experience as is lack of access by public transport. And one should never forget the cost for a family of a boosted interaction due to a coffee, snack or meal in the gallery’s café or restaurant.

All these features, we must remember, are not necessarily for the benefit of the experiencer, for improving our interaction with art. Many exist for the benefit of the art exhibited within the container or for the container (its owners) itself: to support longevity, to maintain or preferably enhance the investment value, and to demonstrate cultural worth and relevance. Such intentions are warranted, but too often come at the expense of the experience of the art. That is why so many people view art, in all its forms, and its experience as the prerogative of a select few, especially the few who have the most resources in society.

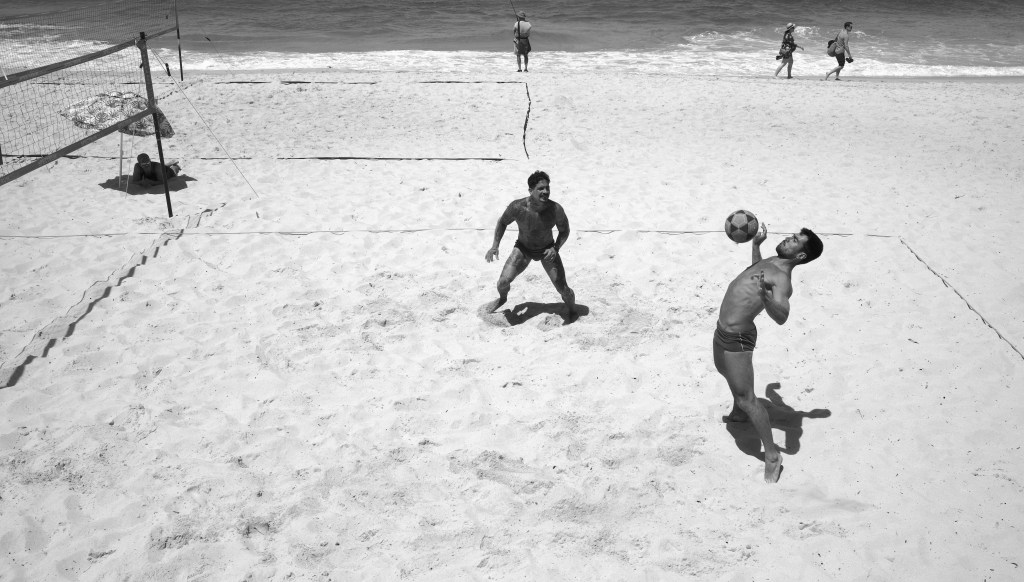

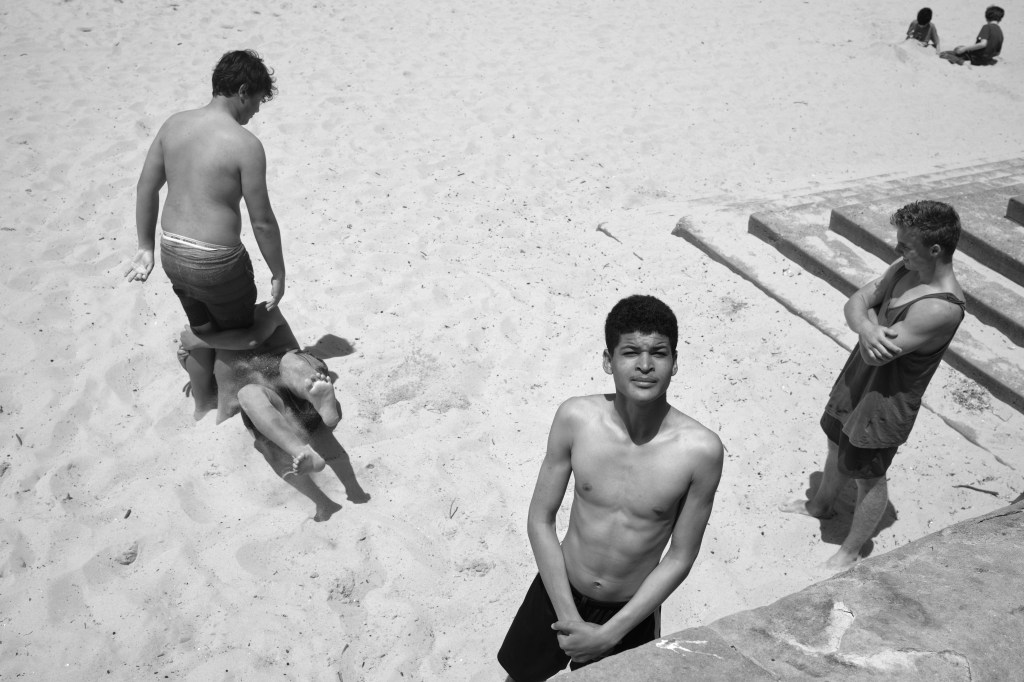

Interactions with art in other contexts—in the home, private galleries, informal spaces, in front of a television or computer monitor/phone/tablet—offer a different range of experiences. Gary colours, bright screens, loud music, movement, crumbs from crisps, the scent of pizza, and so on. Experiencing and interacting with art in these contexts is more under our control than it is in public galleries. And the art itself is often quite different from that held in galleries, more relevant to the experiencer. But the art is not, in itself, necessarily of lesser quality or value even if it is mediated by technology: it is merely different, reflecting different experiential needs, different priorities and different values in life.

As a society we all need to experience art in some form but in our own way and on our own terms. Art can take us away from our daily challenges, can satisfy creative needs and give us insights into the workings of different minds. Even art that does not satisfy has its place: it reminds us of the complexity of life and of the society in which the art is created.

Which do you prefer for interacting with art, greater galleries, lesser galleries, informal contexts? All of them? Or is art something for others to interact with, not for you?